Jason Spezza and the thankless job of Ottawa Senators Captain

"Do you want me to stop the ones going wide, too?" - Tom Barrasso

Jason Spezza is finding out, as Daniel Alfredsson found out before him, that there's some downside to being the captain of the Ottawa Senators.

Back before Daniel Alfredsson was Alfie, before the debacle of his departure, he was a guy with a target on his back. Too many playoff losses to the rival Toronto Maple Leafs. Too many early playoff exits. Too many teams that should have flown higher than they did--teams with Alfredsson as their leader. And all of this was laid at his feet. He was the wrong guy to lead the team, he was too soft on the puck, he was not a vocal enough leader, he was not emotional enough to fire up the team, etc. There was a time when the desire to trade Alfredsson was real. It was only by weathering that storm--by facing the music after he guaranteed a Cup win and didn't deliver, for example--that he came to reach such a legendary status that it could be so easily tarnished by even the slightest... slight. He became so idealized that Sens fans didn't want to acknowledge there was a man behind the curtain.

Does Jason Spezza have to go through the same thing?

It would appear so. In today's Senators Extra section of the Ottawa Citizen, Wayne Scanlan writes:

Not much ownership on the play by the captain.

"The play" in question here is the overtime turnover that led to James Neal's game-winning goal for the Pittsburgh Penguins. Per Scanlan, here's what Spezza had to say that prompted the above criticism:

"The puck was just on the wall, there and Neal lifted my stick. [Greening], I think, went for a line change, didn’t realize they had the puck. So, just a bit of a miscue. It happens. I think he’d been out there for a while. Andy makes a good first save but the puck squirts right to them."

But there's a problem with suggesting that Spezza didn't take ownership on that play based on that quote: What Spezza said was both honest and accurate.

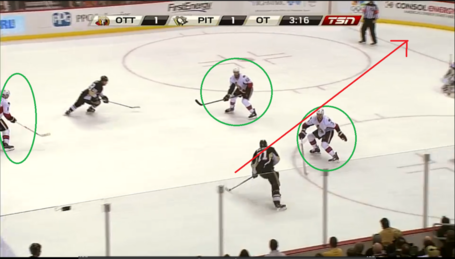

Here's the start of the play in question. In frame are two Penguins players: Evgeni Malkin, the puck-carrier, and James Neal, the eventual goal-scorer. For the Senators, Spezza is just entering the zone, while Eric Gryba and Marc Methot are back to defend.

Colin Greening is behind the play--he is finishing a shift with Z. Smith, Jared Cowen, and Erik Karlsson. Greening had gained the zone and acted as a forechecker to allow his teammates to get off of the ice.

Greening does his job effectively--he gets the puck deep to allow for a change. The initial breakdown on the play occurs when he is unable to catch up to the puck before Pittsburgh gains possession. There's not much blame to assign here per se, as this is a pretty typical hockey play--Greening's linemates are changing, which was the whole point of the dump-in, and it's impossible for Greening to forecheck two different players. Pittsburgh is able to break out effectively because the 4-on-4 format creates more open ice for the players.

Paul Martin (#7 in frame) will take possession of the puck behind his own net and Greening will pursue the puck carrier. What Greening cannot control is Neal (top of frame) looping around the net with speed up the boards at the bottom of the frame. Greening can only attack one man, and he chooses the puck carrier, and this is the correct choice. Martin is forced to curl back to avoid Greening's check, but he is able to spot a streaking Neal and pass to him in full stride.

Neal is able to fill the empty space in Ottawa's zone because while it would typically be Greening's assignment, he was forechecking in Pittsburgh's zone. This leads to the formation we see in the first picture: Defensemen in position, Spezza in position, and a hole where Greening should be. Remember, there's nothing inherently wrong with this--it's a consequence of 4-on-4 hockey. Neal drops the puck for Malkin and cuts to the center of the ice, but Greening's work has given Gryba and Methot time to position themselves in a defensively stable alignment. Methot is in Malkin's shooting lane, and should he attempt to pass to Neal, Gryba is one full stride away from destroying the Penguins forward.

With no trailer to attack the open space Ottawa has given up, Malkin makes the best play he can: He shoots. To describe this as a low-percentage shot is generous--it does not even make it on net. Instead, it goes high and wide, deflecting off of Methot, as indicated by the red arrow.

And this is where things really go like Spezza originally described. Up to this point, while not optimally positioned, the Senators have not been in any danger. Malkin's shot will go wide to the side where the Senators have the numbers. There remains little danger: Neal will have to beat both Spezza and Gryba to retrieve the puck, and Spezza has inside position on Neal to gain possession anyway.

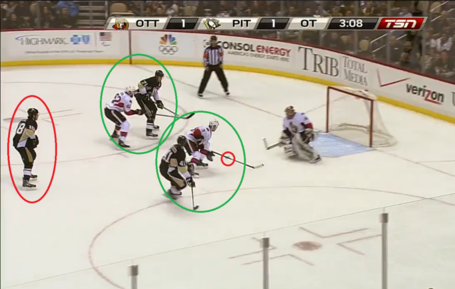

This is exactly what happens.

We can see here that Greening is watching Spezza, and also that Neal is in the process of lifting Spezza's stick. The next frame makes this more clear.

Greening can clearly see this, but he can also see that Gryba is in position to assist Spezza. It's way past the end of his shift, so he calls for a line change.

What Greening doesn't see--and can't be expected to see--is that Neal chops the puck just a half-second before Gryba. Gryba still plays his man, so it's not a lost cause, except that Malkin, who has been trailing behind his original shot (and, who, technically, is Gryba's assignment), is now uncovered. Methot cannot chase the puck on the boards there--he would leave the entire rest of the ice uncovered. That leaves Malkin free to pick up the loose puck, and the Senators with just three men on the ice thanks to Greening's change.

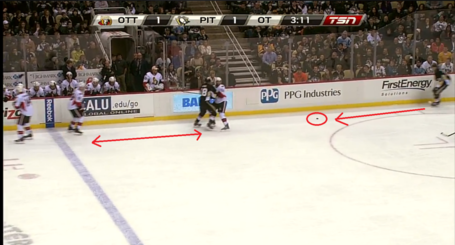

Methot remains in position to cover Malkin--never a bad idea--but as mentioned, this leaves almost all of the ice open for other Pittsburgh attackers. Anderson recognizes this immediately, calling it out on the ice, but it's a no-win scenario for Methot. He absolutely cannot give ground to Malkin, and with no other defenders left, he has to leave Anderson one-on-one with the shooter. This, too, is the right decision, even if it's a damned-if-you-do situation: The shooter is defenseman Robert Bortuzzo--not exactly Sidney Crosby.

Anderson makes the save on Bortuzzo, but by now things have broken down. Methot and Gryba continue to play defense correctly--Methot disengages with Malkin to attack Bortuzzo, and Gryba attacks Malkin, dealing with the two most immediate threats.

But Neal had already become separated from Spezza, and the gap is too large to close before he gets possession of the puck.

And here's the crux of the matter. As we can clearly see from the game clock in the images above, all of these things occur in the span of three seconds. Neal, who knew he was going to attempt to strip Spezza of the puck, is already in the act of stopping, and is engaged with Gryba to additionally slow his momentum. Spezza's momentum continues to carry him backwards as he turns around to locate the puck. But by that point, it's too late, and Neal is able to pull around a handcuffed Anderson and shoot around Methot for the game-winning goal.

So, what's there for Spezza to take ownership of here?

That he was unable to catch up to Neal in a 3-second footrace where Neal had a 15-foot head start and was starting from a dead stop while Spezza was still moving backwards? It's around 50 feet from where Spezza has to start skating to where Neal picks up the loose puck in the middle of the circles. I'm not even sure Erik Karlsson--the team's most explosive skater--could cover that distance in less than 3 seconds starting with backwards momentum. I'm not sure any human could. When two objects start with divergent momentum, the one with the momentum in the right direction has the advantage.

That he had his stick lifted? He owned up to this in the quote. The criticism here seems to be that Spezza wasn't "hard enough on the puck" or something similar--but that doesn't acknowledge the situation. Spezza wasn't in a puck battle. He won the puck through good positioning and then lost it through a sneaky play, not a contest of strength. There's nothing for him to be "hard" on. There's no call for Chris Kunitz to be "harder" on the puck on this play, for instance:

And neither can Kunitz catch up to Turris before he gets a shot away. That's because getting pickpocketed from behind just isn't a consequence of carelessness or losing a puck battle. It's not a symptom of poor leadership or lack of competitive effort. It's what happens when you put highly-skilled players on the ice together.

That he threw Greening under the bus? Did he? The fact is that this play begins in the gap that Greening leaves on the ice, and that had Greening changed sooner, there would be a forward both there to stop the play from developing, and available to cover Neal. But that doesn't mean that Greening made a poor decision or is responsible. It's a miscue--exactly what Spezza said--and if Ottawa gets possession of the puck cleanly, Greening is doing the right thing. Spezza is not calling out Greening for making a bad change--we've clearly established that Greening was not--he is merely explaining why the team only had three players on the ice, and no one available to cover Neal. I don't hear blame in that quote, only an explanation.

The bottom line here is that this goal was the result of a few cumulative mistakes. None by themselves were back-breaking, but added up they make for an unfortunate result. And it's important to keep in mind that turnovers and odd-man situations are exactly what the 4-on-4 overtime is designed to create, and that's what happened last night.

Blaming Spezza for that is misguided.

Spezza has always been a whipping boy in Ottawa, and with the C on his jersey will be an even greater target for criticism--especially with the emergence of Kyle Turris. That means some will write this article off as Spezza apologism. It is nothing of the kind. I totally advocate criticism of players and coaches--when it's deserved. This is a case where I think criticism towards Spezzais undeserved--there's no one to fault on this play. It's a series of small mistakes, and in the NHL, those often wind up in your own net.

In the end, there are probably portions of the game last night where you could suggest that Spezza could have competed harder--perhaps someone with more time and better camera angles can go through each shift and do so. But suggesting that he was culpable, or should take ownership, on the game-winning goal is neither accurate nor fair.